An updated analysis of data captured by NASA’s Cassini Mission, led by NASA scientists and researchers from the University of Washington, has decreased the chances of a subsurface ocean on Saturn’s moon Titan but potentially increased the chances of finding extraterrestrial life.

While the new analysis also suggests that more complex life forms may have difficulty surviving in the slushy environment they suspect lies beneath Titan’s icy surface, the researchers suspect that smaller pockets of water could increase the overall chances of finding simpler life forms like those found in Earth’s polar environments.

a Main Target in the Search for Life Beyond Earth

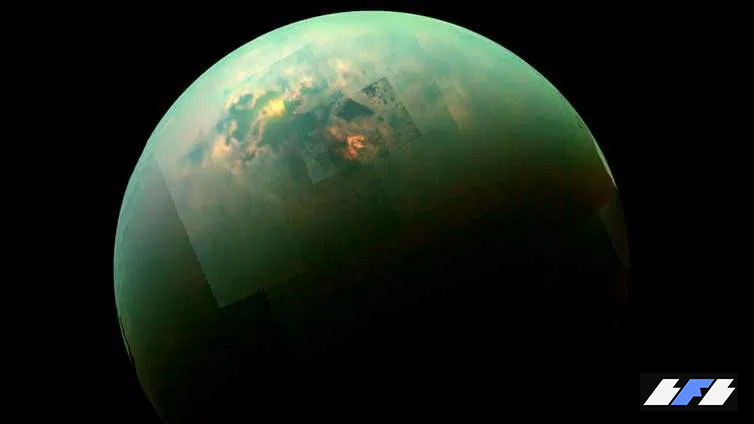

One of 274 moons orbiting Saturn, Titan has long fascinated scientists due to its unique surface features. For example, Titan is the only solar system body besides Earth that may potentially have liquids on its surface, in the form of methane and ethane. The moon also experiences periodic rainfall, making it the only moon known to experience precipitation that reaches its surface.

But unlike Earth’s oceans, Titan’s lakes, rivers, and rains are made of hydrocarbons such as methane and ethane, not liquid water. When combined with its icy surface temperature of –290 degrees Fahrenheit (–179°C), it is considered unlikely that life could exist in any of those liquid environments.

When NASA scientists first analyzed data from Cassini’s decade-plus mission to Saturn and its moons, the initial readings suggested that a large, liquid-water ocean may exist beneath Titan. The discovery fueled speculation about possible extraterrestrial life forms living in such an ocean, including whether more complex life could exist under such conditions.

More recently, evidence has mounted that several other solar system moons, including Saturn’s “Death Star” moon Mimas and Jupiter’s Ganymede and Europa, may also have massive seawater oceans underneath their icy shells. Those discoveries have once again increased optimism that future missions to those space bodies could discover the first irrefutable evidence of life beyond Earth.

New Models Predict ‘Slushy’ Interior Instead of a Liquid Ocean

In the new analysis, the team set out to characterize Titan’s potential subsurface ocean. Specifically, they wanted to understand the degree to which the moon stretches in response to Saturn’s gravitational pull and the duration of that stretching to determine the energy required. The team said this is critical because the moon’s stretching was the first major clue that led researchers to propose the possibility of an ocean back in 2008.

“The deformation we detected during the initial analysis of the Cassini mission data could have been compatible with a global ocean,” explained Baptiste Journaux, a University of Washington assistant professor of Earth and space sciences.

Still, the researcher explained, the moon’s “degree of deformation” depends on Titan’s internal structure.

“A deep ocean would permit the crust to flex more under Saturn’s gravitational pull, but if Titan were entirely frozen, it wouldn’t deform as much,” Journaux said.

Where previous models had supported the possibility of an ocean beneath Titan, the team’s newest models added a component not included in earlier versions: the timing of the deformations. The NASA-led team said that adding this variable was critical, since a closer analysis of the Cassini data showed that Titan’s most considerable deformation occurs roughly 15 hours after Saturn’s peak gravitational pull.

After adding this delay to the updated models, the team found that much more energy was being dissipated in Titan than previously estimated. This increased energy dissipation allowed them to make more informed inferences about the moon’s interior structure. Specifically, the long deformation delay indicated the interior structure was much thicker and viscous than simple water, since more energy was needed to cause a change in Titan’s shape.

“Nobody was expecting very strong energy dissipation inside Titan,” said the study’s leader, Flavio Petricca, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “That was the smoking gun indicating that Titan’s interior is different from what was inferred from previous analyses.”

Journaux said the results suggest Titan’s icy surface has a thick, slushy layer beneath that requires more energy to deform than water does.

“Instead of an open ocean like we have here on Earth, we’re probably looking at something more like Arctic sea ice or aquifers,” the researcher explained.

Improved Odds of Finding Extraterrestrial Life?

When discussing the new analysis, Journaux said that a slushier Titan interior could have “implications for what type of life we might find.” For instance, a thicker or more viscous environment might lead to nutrients gathering in small areas of water rather than being dispersed throughout an entire global ocean. The team said this increased nutrient density could “facilitate the growth of simple organisms.”

The new model also suggested that these theoretical pockets of nutrient-dense water could reach 68 degrees Fahrenheit in highly localized, transient briny areas under specific conditions, influenced by Saturn’s gravity. The researchers said this warmer environment could also increase the chances of extraterrestrial life on Titan.

“The discovery of a slushy layer on Titan also has exciting implications for the search for life beyond our solar system,” Journaux said. “It expands the range of environments we might consider habitable.”

The team said their updated models suggest that future missions to Titan, such as NASA’s Dragonfly Mission, which includes Journaux as part of the team, may not discover “fish wriggling through slushy channels.” Instead, if a future mission does find signs of life on Saturn’s enigmatic moon, it may resemble the simpler life forms found on Earth’s polar ecosystems.